I’ve never regretted a day on the trail. Until today. Now, I haven’t been wheeling all of my life. I haven’t even been doing it for a full decade. But as with any set of complex skills that require learning by doing, I’ve had my share of “bad days” on the trails. There are many things I would have done differently. Different lines. Different execution. Different attitude. But not once did I seriously wish I’d been somewhere else.

I’ve never regretted a day on the trail. Until today. Now, I haven’t been wheeling all of my life. I haven’t even been doing it for a full decade. But as with any set of complex skills that require learning by doing, I’ve had my share of “bad days” on the trails. There are many things I would have done differently. Different lines. Different execution. Different attitude. But not once did I seriously wish I’d been somewhere else.

That’s all changed. I made the trip from Seattle to Portland to spend some time with an old friend in my favorite offroad area, the Tillamook State Forest. I was hoping too, also make some new club friends as I joined them in exploring an area of the forest in which I’d never been.

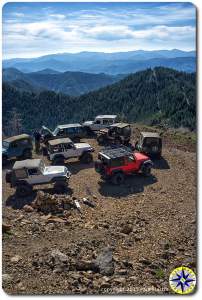

The day started out promising with a short, middling 4×4 trail to get warmed up, followed by some forest roads — including crossing a few of the sizable snow fields that remained. The rest of the day was spent engaged in serious, nearly non-stop vehicular bushwhacking through massive overgrowth down The Road (much) Less Traveled.

I can see the eyeballs rolling. Pinstripes. Big deal. This is just part of the bargain, wheeling forest trails in the Pacific Northwest. But this was different. This was not (now) a trail so much as a glint of a promise of an opening through birch and fir groves. Neither was this a matter of the occasional stripe. Imagine, instead, an automated car-wash in which the brushes have been replaced by (say) blackberry — or angry wolverines. Or maybe, think of polishing your truck with a line trimmer. You get the idea. And then there are the ragged stalactite limbs of blow-down triangulating on the trail, threatening to tear through the soft top. Ten hours of driving (round trip) to take a beating like this on a mostly unmaintained trail? I don’t think so.

Well, so, why? Why continue? That’s a terrific question, for which I don’t think there’s a single answer. Part of it, I think, is the lemming-like inertia associated with finding oneself in the middle of all of this, in the middle of a pack, with no easy way out. But more on this later.

Another part of it has to do with trust, or better, with charity: with the idea that, however bleak things seem at the moment, it can’t go on like this. And, further: there must be some fantastic trail or vista or other compensating good not otherwise obtained.

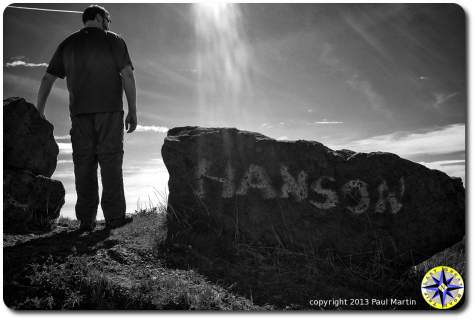

These expectations were soundly thwarted on all fronts. It could go on like this — and did. There was no other trail; this was the trail. Happily, the trail did lead to a quite spectacular view, which but for the marine layer, would have afforded a view of the Pacific, as well as Mounts Hood and Rainier and St. Helens. But this very view could have been easily obtained, minus the risk, by a mere 13 or so miles of forest road capped by a few hundred yards of significantly less overgrown and clearly much more frequently traveled trail.

And so the path taken was unnecessary for attaining the splendid vista, and along the way presented but one or two brief sections that posed much technical challenge. (Whatever else it might be, the challenge of separating paint from body by navigating through heavy brush is not itself a test of driving skill. Avoiding obstacles lining the narrow trail while tending to the distraction posed by overgrowth is another thing entirely.) But then the certain risk of even cosmetic damage was wholly disproportionate to attaining that wonderful view. And of course there are many other trails in the Tillamook State Forest OHV system that offer vastly more technical bang for the buck (and across all skill and experience levels) as well as providing spectacular vistas.

Certainly the journey is at least as important as the destination. And some destinations are very fine indeed. But not just any route is warranted by the destination, however fine. And some routes, perhaps, are less traveled for good reason.

http://youtu.be/keDIJ5iNUls

OK. Deep breath. Now, exhale….

Venting has its place (and not just with brake rotors), but one of the things that’s always appealed to me about wheeling is the pace. And it’s a pace that — or me, anyway — lends itself well to reflection. And both in, and after, this experience, I’ve reflected a bit on the relationship between trail leader and participant.

Of course, the role of the trail leader is not one but many. (These many roles can effectively be distributed across multiple individuals in a group, as it’s a rare individual indeed who can do them all well. But that’s a story for another day.) And these roles involve trip preparation as well as situational thinking at run time. Among the former are to ensure, so far as reasonable, that prospective participants have (among other things):

- suitable equipment

- desired experience

- appropriate expectations

for the trail(s) to be run.

Tuning expectations could be as simple as noting in a pre-run email — or at least in a drivers meeting before hitting the trail — that the route to the run’s destination hasn’t been maintained since Land Rover stopped producing Series trucks, and consequently that on a pinstripe scale from 0-5 (5 being the worst), this one goes to 11.

This sort of informative, relevant pre-run communication is simple, cheap and relatively painless. Leaders can use follow up email (as needed) to further probe prospective participant’s level of preparation and experience. Prospective participants can use the information to gauge interest, self-assess their own preparedness — following up with the run leader as needed — and, perhaps, to opt out.

On this run, alas, the information that would have been most salient for me went without saying. No content rich pre-run emails. No real drivers meeting. Nothing of note communicated over the radio during the run. I do remember, however, before we launched into the warm-up trail (which was completely bereft of pinstripe opportunities), the trail leader strolling past the truck and saying something about enjoying pinstripes half under his breath. I didn’t know then what was to come.

Salient for me. For me. That’s it, isn’t it? Where am I in all of this, as a participant? I’m not at all shy, really, of the realities of wheeling in the forest. And yet on this run my expectations were dashed, with all of the side effects that ensued — not the least of which was a thoroughly unenjoyable day.

So what’s my role in this unhappy chain of events, or, at least, what should it be? Well, pretty clearly the right model of the leader/participant relationship here isn’t an active – passive one. This is sometimes easy to forget; it’s can be seductive to leave the “work” to others and just settle in and cruise. Ultimately we are responsible for ourselves on the trail (as elsewhere): picking a line, recovery, trail repair, food and water and shelter — and speaking up when things seem sideways.

As with trail leadership, this can start well before ever setting rubber to dirt — e.g., by asking questions when relevant bits of information haven’t been explicitly provided:

- What trails will we be running?

- What specific challenges and/or risks should I plan for?

- What can I expect more generally?

If something comes up on the trail, stop and say something. Don’t let it pass over in silence and just hope it works itself out.

The bottom line is, participating on a run is no more passive than leading one. (And leading one responsibly isn’t at all passive, and it’s certainly more than providing an opportunity to play Follow the Leader.) Really, we are all collaborating on a successful run, even as we play different roles.

I wrote above that I find the pace of offroading to lend itself nicely to reflection. This reflection, in turn, can lead to self-discovery. For myself, on this trip I learned that sometimes there are limits to what I’m willing to endure; and that sometimes (as in other areas of my life) I can be too passive and less than sufficiently assertive (which of course isn’t a license to be a tool ;). Perhaps this doesn’t resonate for you. Good. But if it does, then as Gibbs once told DiNozzo, “Don’t be like me. Learn from it.”

Note about the Author: Paul Martin, often referred to as Other Paul on this website contributed this story. Other Paul has years of experience wheeling Toyota FJCs and 80 series and these days pilots a Land Rover Defender 90. He has been a key part of many of our adventures including the Utah Backcountry Discovery Route, Washington Backcountry Discovery Route and many local trail runs. Every opportunity to wheel with Other Paul is an opportunity to learn.