I am finally ready to talk about Venezuela. This ill-advised road trip took place in March of 1983. It was one of those trips that occurred amid a perfect storm of will, an injection of funds from an outside source, availability of time, and the stupidity of youth. As time passes, the more I think of the good that came from it the more I realize that fate is a wonderful thing.

I am finally ready to talk about Venezuela. This ill-advised road trip took place in March of 1983. It was one of those trips that occurred amid a perfect storm of will, an injection of funds from an outside source, availability of time, and the stupidity of youth. As time passes, the more I think of the good that came from it the more I realize that fate is a wonderful thing.

It was after 11:00 p.m. when the call came. There had been several days of conversation about whether or not I should come to Venezuela. I wanted to go, but not alone. My host wanted me to come. I couldn’t afford it. Neither could my travel companion. The question was how badly did our host want us? At 11:00 p.m. the night before our departure we learned that he wanted us bad enough to pay for our air fare, pick us up and house us even though it was not under the best of circumstances that we were traveling. Me, to have legal documents signed that would negate a partnership. Our host’s motives, I presumed were to try and talk me out of it. For lack of a neutral venue, I went. 21 years old and not very worldly, albeit utterly confident I could navigate any waters the tide brought in.

My best friend and I flew to Miami with a Venezuelan who gave us tips all of the way to the point we separated in the Miami airport about the cultural dos and don’ts we should understand before our arrival, how to get through customs flawlessly, how to greet our elders, how to not stick out like two naive American girls on their first trip abroad; the basics. We listened intently until we boarded our flight to Caracas where our confidence waned and an underpinning of fear for our future set in as we lifted a used newspaper from our assigned seat in the plane and saw the head line that read, “American Woman Held on Drug Trafficking Charges in Venezuelan Prison.” We looked at each other wordlessly trying to assure ourselves that we’d made the right decision 18 hours earlier to take this trip, both knowing that the woman charged in the article was very likely innocent and that it would be months if not years before she was released. My companion broke the silence with an uneasy, “Well, we’re not trafficking drugs, so there’s that.” Our future in the hands of fate, the flight took off over the Caribbean.

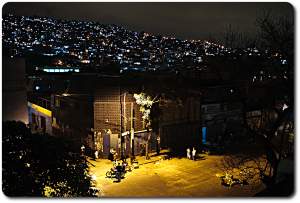

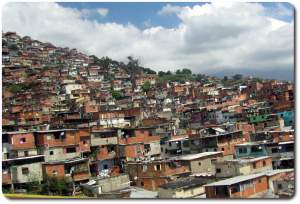

We arrived in the night and were met by our host and a friend who turned out to be our driver. From the airport to Los Palos Grande where we would spend our first nights, we watch the thin outline of the mountains against the night sky dotted beautifully by tiny lights. We commented at how pretty it was. Our comments were greeted by snickers that we didn’t understand and protested, “You don’t think it’s beautiful?” Our host responded that perhaps by night it was but in the light of day it was quite something else and we would see. It was true. By the light of day what looked like rows and rows of prettily lit streets and houses was a settlement of Columbian Indian refuges that’d fled over the mountains and settled by the thousands in makeshift tin and cardboard shacks along the side of the mountains. The Beautiful lights were an irregular confusion of wires tangled together that strung for miles back and forth across the face of the mountain to provide an amount of light and security to the inhabitants beneath them.

We arrived in the night and were met by our host and a friend who turned out to be our driver. From the airport to Los Palos Grande where we would spend our first nights, we watch the thin outline of the mountains against the night sky dotted beautifully by tiny lights. We commented at how pretty it was. Our comments were greeted by snickers that we didn’t understand and protested, “You don’t think it’s beautiful?” Our host responded that perhaps by night it was but in the light of day it was quite something else and we would see. It was true. By the light of day what looked like rows and rows of prettily lit streets and houses was a settlement of Columbian Indian refuges that’d fled over the mountains and settled by the thousands in makeshift tin and cardboard shacks along the side of the mountains. The Beautiful lights were an irregular confusion of wires tangled together that strung for miles back and forth across the face of the mountain to provide an amount of light and security to the inhabitants beneath them.

This wasn’t our first indication that we weren’t in Kansas anymore. When we’d arrived the night before we were taken to an apartment building where our host family lived in a two bedroom apartment. The front door of which was a steel cage, the equivalent of a cell door in a prison. Inside of the first door a second flat steel door shut out the world. Both opened and closed through the sole use of a key. That first night as everyone slept more than thirteen floors up, I lay thinking, if there is a fire, who will find that key and let us out? It doesn’t matter. There is no way this building is to code. We’re all dead. I didn’t want to be rude to my gracious hosts but I needed to get out of this death trap.

During the course of our first day my business of dissolving our partnership had been completed. Surprisingly with little resistance, which I attributed to the family of our host, who unanimously agreed with me it was for the best. This left an entire week ahead and us looking stupidly at one another wondering what next. My travel companion suggested we rent a car and tour the country. Having come from the land of free to move about as you please, it never occurred to us that what we suggested was easier said than done. We’d seen a car rental shop in the storefronts that lined the first floor of our building; we knew how to read a map. I spoke a fair amount of Spanish. How hard could it be? Judging by the scuttle our suggestion caused, very hard. It was clear that there was no way our host’s family was going to let two young American girls travel unchaperoned around the hazardous and wild roads of Venezuela. Our host was volunteered to ride with us. For my travel companion and I this was less desirable, given that it was his irresponsible nature that had brought us to Caracas to begin with.

During the course of our first day my business of dissolving our partnership had been completed. Surprisingly with little resistance, which I attributed to the family of our host, who unanimously agreed with me it was for the best. This left an entire week ahead and us looking stupidly at one another wondering what next. My travel companion suggested we rent a car and tour the country. Having come from the land of free to move about as you please, it never occurred to us that what we suggested was easier said than done. We’d seen a car rental shop in the storefronts that lined the first floor of our building; we knew how to read a map. I spoke a fair amount of Spanish. How hard could it be? Judging by the scuttle our suggestion caused, very hard. It was clear that there was no way our host’s family was going to let two young American girls travel unchaperoned around the hazardous and wild roads of Venezuela. Our host was volunteered to ride with us. For my travel companion and I this was less desirable, given that it was his irresponsible nature that had brought us to Caracas to begin with.

Regardless, if I was to escape sleeping another night in a prison cell awaiting sure death by fire, he would have to accompany. We acquiesced. It was decided that we’d head to the coast and Tucacas and Chichirivichi and beaches there. If we couldn’t find a place to stay, we’d sleep on the beach. We were off.

No sooner had we left the metropolitan area on the road west of Caracas than we were met by wobbling buses full of workers and passed women awaiting these buses on the side of the road with livestock. We passed small banana stands and stands with other fruits. Within an hour, we passed kids our age hitch hiking; two boys and a girl. Our host stopped. I looked at my friend and she looked at me. We looked at our host. “We’re not picking them up?” We were. They piled in and we learned that the two boys were friends. They were headed to a parent’s condo near the beach and for a ride we could stay the night. As for the girl, they didn’t really know her. They’d picked her up along the way. Given her dress and deportment, she forever became known to Karon and me as the prostitute. We never did know her name.

It was evening when we arrived at the condo of the boys. We’d driven through villages were pigs wallowed in mud in the streets and rooted for food and where chickens scratched freely in the dirt. The roads narrow one lane dirt tracts that no municipal branch maintains. We’d passed dense jungle swaths dotted with leafy shacks along the roads, and perhaps many others hidden by the flora. We arrived almost suddenly in an community of well-groomed newly built structures that were clean and landscaped, where the roads were paved and wide enough for two lanes and for cars to park at the curb. The difference in scenery so sudden, it was confusing. We ate, laughed, drank, and danced until late in the night and then we slept in comfortable beds with fresh clean linens and our host’s final glance at us was a knowing, ‘told you so’ look that implied this was how it was done. That is until the next morning when we awoke to shrieks.

The hitchhiking boy’s parents had arrived to find a house full of strangers and a floor three inches deep in water. Someone had turned on a faucet and never turned it off. The rapport of angry Spanish fired at the boy in the next bedroom was indecipherable and was our cue to leave. We ran. The three of us ran without good-bye to the boy or his family, and we took the prostitute too. It was ten minutes of driving before we even bothered to ask where we were going. Our host answered, “The beach.” We relaxed. What could go wrong at the beach… (continued “To Venezuela… and Beyond – Part 2 out of the frying pan & into the fire“)