…Our host’s father assured us that we would but first we were going to dinner.

…Our host’s father assured us that we would but first we were going to dinner.

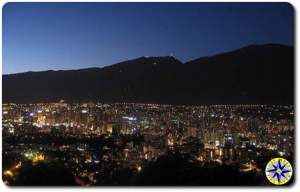

We all piled into the rented car and drove into the mountains that surround Caracas until we came to a beautiful white ranch styled home that looked up the valley in which Caracas is built. From this vantage, we could see the entire expanse of the beautiful city lit in the evening darkness. The view was breathtaking. The inside of the house was completely empty, save for several cardboard boxes that had remained from when the inhabitants had moved out. The back of the house that faced the city was a series of large rooms with sliding glass doors so that from every room one could see the panorama of the city that lay below it. Each door opened to a wide shared patio made of slate where our host’s mother had arranged cardboard boxes into a table and chairs and where she was setting the table with paper plates. Just as she finished, his father came from the back of the house with a boxed pizza they’d had delivered and we all sat down and ate while he explained what this house was. It was theirs. “If this is your house, why do you live in the apartment in the city?” I asked. A look of sadness swept over the faces of the parents. Pride had been abandon. “Our son has bankrupted us.” We looked at our host, me fighting the urge to send him my most cutting ‘how could you’ look. His father went on to explain how it happened and I was reminded of a time when they came to the U.S. to visit us. The father and I had gone for a pleasant walk together. He’d asked me about his son, what he spent on me, what gifts I’d received from him, how he spent his money. My responses didn’t help him as my answers were, nothing, none, and I don’t know. I think the man thought his son was lavishing me with expensive gifts, cars, a place to live perhaps? No. The boy, whose money I thought belonged to him, that he spent on cars, a condo, musical equipment, clothes, and I couldn’t say what else, was spending his father’s money. He’s spent every penny of it.

I had to ask. “Did you pay for our flight here this week?” The parents looked at each other and then at their son. “I’ll pay you back as soon as I can.” I hastened to say. To which they responded in unison. “No. You won’t. It is our pleasure to have you here.” They didn’t know their son had paid for our trip. We ate our dinner and chatted on about much more benign things.

It was late when we returned to the apartment in Los Palos Grande. Karon had been patient but it was after ten and she was beginning to feel desperate about calling home and assuring her mother that she was still alive. I was not so concerned. I hadn’t bothered to tell my parents, or anyone else in my family for that matter that I was going. Her anxiety was palatable. Our host’s father suggested that he drop off his family and take us to make our call. We had no idea what he meant.

We left his wife, teenaged and preschool aged daughters at the door of the apartment building and he instructed his son to drive. Moments later we arrived at the equivalent of the AT&T building in Caracas. “Turn the lights off. Drive around back.” He instructed. “Park here by this door.” We did. We got out in an ally at the back of the large building and he knocked on the door. Karon and I shared uh-oh glances, realizing by now that nothing every goes easily here in this place of rugged terrain and uncertain living. The door opened.

We left his wife, teenaged and preschool aged daughters at the door of the apartment building and he instructed his son to drive. Moments later we arrived at the equivalent of the AT&T building in Caracas. “Turn the lights off. Drive around back.” He instructed. “Park here by this door.” We did. We got out in an ally at the back of the large building and he knocked on the door. Karon and I shared uh-oh glances, realizing by now that nothing every goes easily here in this place of rugged terrain and uncertain living. The door opened.

A security guard let us in and led us to a switchboard room. He stopped us in front of a row of switch boards and asked, “Who needs to make a call?” Karon stepped forward. He asked her questions and as she responded, he worked. At last he handed her headphones with a mouth piece and told her, “You have three minutes.” She took the headset. “Hello?” she asked. Her shoulders relaxed and fear and anxiety washed from her brow. She was talking to home, a place I suspected she never appreciated more than she did at that very moment.

When the call ended, she fired me a warning glance. “You’d better call home too. Your parents are freaking out. They called my mom and she told them where we are.” I looked at our host. He nodded to the guard and the call was made. Unlike Karon, my call was much less a relief. I didn’t use my full three minutes. My parents asked if I was ever coming home. I said I was. They hung up on me. It was an easier call than I had anticipated. Note to self, next time call from the Miami airport and have this conversation before you leave.

Mission accomplished, we paid the guard the equivalent of twenty dollars and slinked back out the employee entrance and home to sleep again in the fire trap, which by now had become much less scary to me. In truth, a fiery death seemed much more palatable than going home.

Mission accomplished, we paid the guard the equivalent of twenty dollars and slinked back out the employee entrance and home to sleep again in the fire trap, which by now had become much less scary to me. In truth, a fiery death seemed much more palatable than going home.

Early the next morning the cousins from the beach arrived with a plan. We’d drive into the mountains to a German Village (similar to but substantially smaller than Torvar and about 5 hours closer to Caracas) and have dinner. We drove into the mountains about four-and-a-half hours, passing towns and often finding ourselves in a stream of cars also creeping up the thin two-lane mountain road. As we climbed the weather cooled. Karon and I began to feel safe in our assumption that something even as placid as a day trip into the mountains for dinner would go anything like a trip we might embark upon in the U.S. We relaxed into a state of fearless acceptance, understanding that we had no idea what to expect anymore.

It was late in the day when we arrived in the village. Dusk had begun to settle in the sky and the village was shutting down. We passed homes that looked Bavarian with kitchen gardens full of fruitful plants and laundry drying in the evening breeze. We passed blond men, women, and children with blue eyes and traditional German attire, the likes of which one would expect to see on a postcard from the Alps. We parked in the center of the village and walked to a restaurant near the edge of it all and were stopped at the door. “We’re closed.”

Hungry and tired from the drive, our spirits sunk. Our host and his cousin begged, explaining who we were and how far we’d come. The result was the suggestion that we come in and eat the one thing they could cook for us in a wood fire stove. Pizza. We cheered. It turned out they were not closed because they wanted to be. They were closed because they could only count on electricity for a few hours a day and wanted to use it in the night for their homes. The restaurant owner’s daughter lit candles and they fired up the oven with fresh wood and served us drinks to bide the time. As the night fell on the little restaurant in the mountains of Germany, oh, no, Venezuela, we talked, laughed and relaxed. The world’s most delicious pizza was served and we ate, talked and laughed more. On the drive home, Karon and I slept peacefully, forgetting that we had only one more day before we were scheduled to fly home.

Hungry and tired from the drive, our spirits sunk. Our host and his cousin begged, explaining who we were and how far we’d come. The result was the suggestion that we come in and eat the one thing they could cook for us in a wood fire stove. Pizza. We cheered. It turned out they were not closed because they wanted to be. They were closed because they could only count on electricity for a few hours a day and wanted to use it in the night for their homes. The restaurant owner’s daughter lit candles and they fired up the oven with fresh wood and served us drinks to bide the time. As the night fell on the little restaurant in the mountains of Germany, oh, no, Venezuela, we talked, laughed and relaxed. The world’s most delicious pizza was served and we ate, talked and laughed more. On the drive home, Karon and I slept peacefully, forgetting that we had only one more day before we were scheduled to fly home.

That final day in Caracas was spent at a country club. This was a stark change in environment from the rest of our trip. Our host’s father knew the manager of the country club where the roster of over 3,000 members came from all over the world. They let us in and ushered us to the pool area. From there we could see the golf course, polo fields, and tennis courts. A waiter brought us what we asked for and we sat in white lawn chairs near the pool relaxing in the sun. From different points around the pool one speaking enough languages could eaves drop on conversations in French, German, Japanese, Spanish and perhaps other languages that my untrained ear couldn’t comprehend. It was opulent compared to the country clubs I’d seen in the U.S. and white. Everything was white. We stayed there, and stayed out of trouble in the clean white peacefulness the entire day. Then we slept one more night in the apartment with the prison cell door.

The next morning we were ready to go. We woke early, packed quickly and presented our host’s parents with gifts we’d acquired in our travels. Karon asked more than once how we were getting to the airport and we learned that the entire family was taking us. Knowing this was a relief. We left early for the airport and got our tickets and our bags checked easily. The family went with us to customs to make sure that there were no issues and at that point we said our good byes. I was suddenly gripped by the finality of this endeavor. I would never see these people again after a very long three year relationship. The idea was overwhelming and I began to cry. We walked toward our gate and the tears continued. I cried until the flight took off and the stewardess took pity on me and offered me a good stiff drink. I took it. I couldn’t decide if the tears belonged to a deep seated love for this family or if they were a physical reaction to the relief I felt for knowing that this period of my life had just ended.

Karon and I flew in silent exhaustion until we were almost to Miami. It was late at night and the captain of the plane announced that our landing would be slightly delayed. He would have to navigate us around a tremendous thunder storm to the west of Miami to avoid the turbulence and circle until we could land. We watched out one window of the plane a most spectacular storm and out the other window of the plane a most beautiful star filled night with a brilliant full moon. The striking difference in views was a remarkable parallel to the worlds we had come from and were going to, to the difference between my life before the Venezuelans, during the Venezuelans and what lay after the Venezuelans. I watched in succession between the two windows and smiled. Life was full of calm starry nights and horrendous thunderstorms and each were spectacular.

Karon and I flew in silent exhaustion until we were almost to Miami. It was late at night and the captain of the plane announced that our landing would be slightly delayed. He would have to navigate us around a tremendous thunder storm to the west of Miami to avoid the turbulence and circle until we could land. We watched out one window of the plane a most spectacular storm and out the other window of the plane a most beautiful star filled night with a brilliant full moon. The striking difference in views was a remarkable parallel to the worlds we had come from and were going to, to the difference between my life before the Venezuelans, during the Venezuelans and what lay after the Venezuelans. I watched in succession between the two windows and smiled. Life was full of calm starry nights and horrendous thunderstorms and each were spectacular.